- ACCADEMIA

IL MURO E LA PORTA

Accademico Alessandro Ivan Battista

IL MURO E LA PORTA

di

Ivan Battista

Ogni muraglia ha la sua porta.

Elias Canetti, La provincia dell’uomo.

Quaderni di appunti, 1942-1972.

(Adelphi, Milano, 1978)

Il muro ha una simbologia polivalente: può contenere, può dividere o difendere o può riportare scritte di frasi, di nomi, può ospitare dipinti. Anche la porta può avere una simbologia polivalente: col suo aprirsi o chiudersi, può indicare la libertà o il passaggio verso un’altra dimensione oppure può costringere e imprigionare, nascondere o svelare.

Dal Kotel, o muro del pianto, al Vietnam Veterans Memorial di Washington D.C., alla muraglia cinese, ai costruiti ed erigendi muri di separazione contro le immigrazioni, il muro ha sempre rappresentato e rappresenta una situazione limite.

In storia dell’arte famose sono nel XVIII secolo (1749/50-1761) le incisioni delle Carceri d’invenzione del famoso incisore e architetto Giovanni Battista Piranesi. Con esse, il Piranesi scatena la sua libertà d’immaginazione e di dinamismo prospettico attraverso la rappresentazione di muri, angoli, portici accennati che inducono nell’osservatore una risposta psicologica di costrizione e di angustia. Il muro è uno spazio bidimensionale spesso adoperato per comunicare. Dalle mani impresse in negativo sulle pareti rocciose delle grotte preistoriche di Pech Merle o di Gargas in Francia, all’affresco del Concerto degli Angeli di Gaudenzio Ferrari nella cupola del Santuario della Madonna dei Miracoli a Saronno (1534-1536), ai graffiti e alle immagini dei prigionieri delle carceri segrete dell’inquisizione spagnola in Sicilia che si trovano nel complesso dello Steri di Palermo, tutte hanno espresso, a seconda, voglia di tramandare asserzione, opulenza, disperazione, potere. È la psiche del Sapiens che si esprime coi e sui muri.

In architettura e nell’arte, dunque, il muro si erge, difende, divide, imprigiona, rappresenta. In psicologia, il muro rimanda alla chiusura mentale, al pregiudizio, al rifiuto egodifensivo come la negazione che non permette al problema psichico di essere ammesso alla corte della consapevolezza, passo soterico e indispensabile per l’avvio del cammino verso la guarigione.

Nel romanzo breve più venduto al mondo: Lo strano caso del dottor Jekyll e mister Hyde di Robert Louis Stevenson, il positivista scienziato dottor Jekyll crede di poter varcare impunemente il muro che si frappone tra l’Io e l’Ombra, intesa proprio in senso junghiano come archetipo contenente il principio del primitivo, non necessariamente male, ma molto pericoloso se non lo si integra con gli aspetti più razionali ed etici della psiche.

I muri, se intesi quali bastioni irremovibili di certezze fideistiche, hanno sempre prodotto lutti e dolore. La fede religiosa, se vissuta in maniera fanatica, è sempre stata ed è tutt’oggi un muro d’intransigenza apportatore di genocidi, guerre e devastazioni. Scrive Immanuel Kant in Per la pace perpetua: “La guerra è un male perché produce più persone malvage di quante non ne tolga di mezzo” (Kant, I. Per la pace perpetua, Feltrinelli, Milano, 2022, pag. 74). Di una guerra infinita, come quella tra gli Israeliani e i Palestinesi o quella tra ucraina e Russia, si usa l’espressione di “muro contro muro” per intendere che non esiste margine per la mediazione, perché nessuno dei contendenti è disposto a cedere porzioni delle proprie ragioni per riconoscere all’altro parte dei suoi diritti.

Il muro contiene la porta che è limen, cioè soglia che divide il di qua dal di là, ma la porta può essere anche “murata”, emblema del non più raggiungibile e del disattivato. Disattivazione che, in architettura ed in ingegneria edile, può essere riattivata con un intervento rigenerativo atto a riconsegnare a nuova funzione lo spazio e la volumetria che erano stati preclusi.

Nella suonata per pianoforte Quadri di un’esposizione del compositore russo Modest Petrovič Musorgskij, poi trascritta per orchestra nella versione più conosciuta da Maurice Ravel, il X brano La grande porta di Kiev esprime una forte solennità. In effetti, l’ispirazione al compositore fu data da disegni e acquarelli dell’architetto e pittore pietroburghese Viktor Aleksandrovic Hartmann. Il progetto della porta di Kiev fu ideato da Hartmann per onorare lo zar Alessandro II uscito indenne da un tentativo di omicidio il 4 aprile 1866. L’architetto valutava il progetto della porta come il miglior lavoro della sua vita professionale. La porta, in questo caso, assume il valore di conferma della vita, di facoltà di ammettere o estromettere ad essa e del ruolo del potere da quella rappresentato. La porta come confine tra il dentro e il fuori, tra l’intimo e il formale, ha sempre assunto un grande significato psicologico. I battenti chiusi custodiscono o nascondono. La porta difende la riservatezza, ma cela a volte segreti inconfessabili, soprattutto agli occhi degli estranei.

Nel suo straordinario saggio sull’icona Le porte regali, Pavel Florenskij ci prende per mano e, con acutissime analisi storiche e riflessioni filosofiche, ci conduce attraverso le “porte regali” dell’iconostasi che segnano il limite tra il mondo del percepibile e quello dell’impercepibile, zona impalpabile in cui avviene l’epifania di un dipingere eccelso in cui le figure sono “come prodotte dalla luce”.

L’ingegnere e matematico Erone di Alessandria, collocabile tra il I e il III secolo dopo Cristo, scrisse due trattati di pneumatica in cui puntualizzò molte applicazioni della pressione. Quella che interessa di più in questo scritto è la cosiddetta macchina di Erone, un congegno pneumatico che permetteva di aprire, e di chiudere le porte di un tempio, apparentemente senza l’intervento dell’uomo. Una versione antica delle attuali porte automatizzate. L’effetto di stupore e di soggezione sui fedeli che affluivano era assicurato.

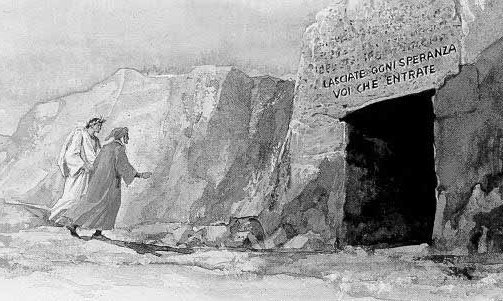

Ultima, ma non meno importante nella nostra cultura occidentale e medievale, è la porta dell’accesso all’inferno, descritta dal sommo Dante Alighieri nell’apertura del canto III della Divina commedia (Edizioni Polaris, Faenza, 1990).

«Per me si va nella città dolente,

Per me si va nell’eterno dolore,

Per me si va tra la perduta gente. (…)

Lasciate ogni speranza, voi, ch’entrate!

Queste parole di colore oscuro

Vid’io scritte al sommo d’una porta: (…)»

La porta, quale soglia del non ritorno, ricorda gli stadi dello sviluppo fisico e del suo ciclo che si “chiude” sulla vita di ognuno con la morte. La caratteristica fisica del soma è proprio quella del cambiamento che non lascia traccia di ciò che era prima il corpo, la cui sembianza precedente va perduta per sempre. Differente è, invece, l’aspetto psichico che cambia anch’esso, ma ha la caratteristica di mantenere, con la memoria, le dimensioni di tutti gli stadi dello sviluppo passato.

Concludo con una bella e famosa citazione relativa al nostro poeta Giovanni Pascoli:

«È dentro di noi un fanciullino che non solo ha brividi (…)

ma lagrime ancora e tripudi suoi. (…) Ma quindi noi cresciamo,

ed egli resta piccolo; noi accendiamo negli occhi un nuovo desiderare,

ed egli vi tiene fissa la sua antica serena maraviglia.»

(Il fanciullino, inizio del I capitoletto, in Giovanni Pascoli, Pensieri e discorsi,

Ed. Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna, 1907).

Come suggerisce James Hillman nel suo Puer aeternus non dobbiamo dimenticare che la percezione del nostro destino e della nostra missione di vita ha radici nel Puer. Il Puer, dunque, quale porta e muro psichici che schiudono, sbarrano e comunicano, soprattutto a noi stessi, il messaggio principale della nostra vita. (James Hillman, Puer aeternus, Adelphi, Milano, 1999).

by

Ivan Battista

Every wall has its door.

The Province of Man.

Notebooks of notes, 1942-1972.

Elias Canetti,

(Adelphi, Milan, 1978)

The wall has a polyvalent symbology: it can contain, it can divide or defend or it can bear writings of phrases, of names, it can house paintings. The door can also have a polyvalent symbology: by its opening or closing, it can indicate freedom or passage to another dimension or it can constrict and imprison, hide or reveal.

From the Kotel, or Wailing Wall, to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., to the Wall of China, to the built and erected walls of separation against immigration, the wall has always represented and represents a boundary situation.

In art history, famous in the 18th century (1749/50-1761) are the engravings of Invention Prisons by the famous engraver and architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi. With them, Piranesi unleashes his freedom of imagination and perspective dynamism through the depiction of walls, corners, and hinted porticoes that induce in the viewer a psychological response of constriction and narrowness. The wall is a two-dimensional space often used to communicate. From the hands imprinted in negative on the rock walls of the prehistoric caves of Pech Merle or Gargas in France, to Gaudenzio Ferrari's fresco of the Concert of Angels in the dome of the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Miracles in Saronno (1534-1536), to the graffiti and images of prisoners in the secret prisons of the Spanish Inquisition in Sicily found in the Steri complex in Palermo, all have expressed, depending, a desire to convey assertion, opulence, despair, power. It is the psyche of the Sapiens that expresses itself with and on the walls.

In architecture and art, therefore, the wall stands, defends, divides, imprisons, represents. In psychology, the wall refers to mental closure, prejudice, and egodefensive denial as the denial that does not allow the psychic problem to be admitted to the court of awareness, a soteric and indispensable step on the path to healing.

In the world's best-selling short novel, Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the positivist scientist Dr. Jekyll believes that he can cross the wall between the ego and the Shadow with impunity, understood precisely in the Jungian sense as an archetype containing the principle of the primitive, not necessarily evil, but very dangerous if it is not integrated with the more rational and ethical aspects of the psyche.

Walls, if understood as immovable bastions of fideistic certainties, have always produced mourning and pain. Religious faith, if lived fanatically, has always been and still is today a wall of intransigence bringer of genocide, war and devastation. Immanuel Kant writes in For Perpetual Peace, “War is an evil because it produces more evil people than it takes out of the way” (Kant, I. For Perpetual Peace, Feltrinelli, Milan, 2022, p. 74). Of an endless war, such as the one between the Israelis and the Palestinians or the one between Ukraine and Russia, the expression “wall to wall” is used to mean that there is no room for mediation, because none of the disputants is willing to give up portions of their reasons for recognizing the other's part of their rights.

The wall contains the door that is limen, that is, threshold that divides the this side from the that side, but the door can also be “walled in,” emblem of the no longer reachable and the deactivated. Deactivation, which, in architecture and building engineering, can be reactivated with a regenerative intervention designed to return to a new function the space and volume that had been foreclosed.

In the piano piece Pictures of an Exhibition by Russian composer Modest Petrovič Musorgsky, later transcribed for orchestra in the best-known version by Maurice Ravel, the X piece The Great Gate of Kiev expresses a strong solemnity. In fact, inspiration for the composer came from drawings and watercolors by the Petersburg architect and painter Viktor Aleksandrovic Hartmann. The design of the Kiev Gate was conceived by Hartmann to honor Tsar Alexander II who escaped unscathed from an assassination attempt on April 4, 1866. The architect rated the gate design as the best work of his professional life. The door, in this case, takes on the value of confirmation of life, of the faculty of admitting or ousting to it and of the role of power represented by it. The door as a boundary between the inside and the outside, between the intimate and the formal, has always assumed great psychological significance. Closed doors guard or conceal. The door defends privacy, but it sometimes conceals unmentionable secrets, especially from the eyes of outsiders.

In his extraordinary essay on the icon The Royal Doors, Pavel Florensky takes us by the hand and, with acute historical analysis and philosophical reflections, leads us through the “royal doors” of iconostasis that mark the boundary between the world of the perceivable and the world of the imperceptible, an intangible zone in which the epiphany of a lofty painting takes place in which figures are “as if produced by light.”

The engineer and mathematician Heron of Alexandria, who can be placed between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD, wrote two treatises on pneumatics in which he punctuated many applications of pressure. The one of most interest in this writing is the so-called machine of Heron, a pneumatic device that allowed the doors of a temple to be opened, and closed, apparently without human intervention. An ancient version of today's automated doors. The effect of amazement and awe on the flocking worshippers was assured.

Last but not least in our Western and medieval culture is the gateway to hell, described by the supreme Dante Alighieri in the opening of Canto III of the Divine Comedy (Polaris Editions, Faenza, 1990).

“For me one goes into the city of sorrow,

For me you go to the eternal sorrow,

For me you go among the lost people. (...)

Give up all hope, you, who enter!

These dark-colored words

I saw written at the top of a door: (...)”

The door, as the threshold of no return, recalls the stages of physical development and its cycle that “closes” on one's life with death. The physical characteristic of the soma is precisely that of change that leaves no trace of what the body was before, whose previous semblance is lost forever. Different, on the other hand, is the psychic aspect, which also changes, but has the characteristic of retaining, with memory, the dimensions of all stages of past development.

I conclude with a beautiful and famous quote related to our poet Giovanni Pascoli:

“It is within us a maiden who has not only shivers (...)

But tears still and triumphs of his own. (...) But therefore we grow,

and he remains small; we kindle in his eyes a new longing,

And he keeps there fixed his old serene wonder.”

(Il fanciullino, beginning of the I capitoletto, in Giovanni Pascoli, Pensieri e discorsi,

Ed. Nicola Zanichelli, Bologna, 1907).

As James Hillman suggests in his Puer aeternus, we must not forget that the perception of our destiny and life mission is rooted in the Puer. The Puer, then, as the psychic door and wall that opens, bars and communicates, especially to ourselves, the main message of our life. (James Hillman, Puer aeternus, Adelphi, Milan, 1999).